Restoring the Coburn Tapestries

The story of how the curtains came to be hung again

John Coburn was at the height of his fame when the artist was pitched to architect Peter Hall to design the Sydney Opera House theatre curtains in 1969. Hall had taken over from Danish architect Jørn Utzon and was ushering the building towards completion.

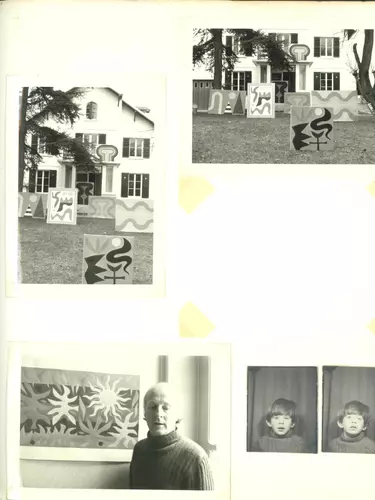

Coburn was a leading Australian abstractionist, known for vivid geometric paintings in a very Australian colour palette that drew on lush botanical sources he had grown up with in sub-tropical Queensland. He did also, as it happened, have experience with tapestries thanks to a collaboration with weavers Pinton Frères in Felletin – close to the more famous Aubusson in France. They had used Australian Merino wool exclusively for the Tapestries, and he was one of the Australian artists they called on to celebrate the connection.

Coburn’s bold designs were stunning. He was inspired by Spanish artist Joan Miró’s ceramic murals for the UNESCO building in Paris: Mur du soleil and Mur de la lune. He named the curtains in similar spirit – Curtain of the Sun for the Opera Theatre (now called the Joan Sutherland Theatre) and Curtain of the Moon for the Drama Theatre – though his artistic style was quite different from Miró’s. The Sun curtain, measuring sixteen by eight metres, was portrayed in hot yellows and reds. The Curtain of the Moon in cool blues and greens, was seventeen by five metres in size. When they were finished in 1971, the tapestries were shipped to Hamburg to be made up into functioning stage curtains before their arrival in Australia. Fifteen months later, at the opening of the Opera House, their sheer size, vibrant colours and striking abstract imagery were an undeniable focus of attention.

The journey to hang the curtains

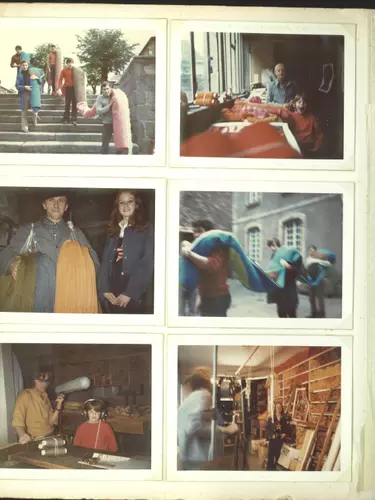

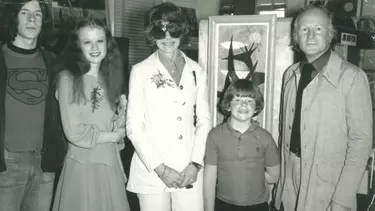

Coburn’s family, including his wife Barbara and children Stephen, Kristin and Daniel, spent three years in France when their father created the tapestries with Pinton Frères. There were hurdles in getting the tapestries up. First, there were problems with fireproofing: the French convention of fireproofing the cotton warp of tapestries but not the woollen weft didn’t suit NSW fire regulations. There were problems with the manufacture. Hall worried about gaps between the coloured shapes; Pinton Frères insisted they would be invisible once the curtains were properly backed. Hall insisted a team of sewers be retained to fill in the spaces and annoyed the French company by demanding it pay them for the additional work.

Once that was sorted and the tapestries were installed, some directors and set designers expressed concern with how the colourful tapestries clashed with the artistic direction of their sets. After a period of intensive use in the busy venues, the tapestries also started to show signs of significant damage including grease stains, burns, rips and tears and as a result, they were decommissioned in the late ‘80s.

At the same time, the build of the Opera House had a long list of problems. Jørn Utzon resigned when the project was only half complete because of intense pressure from the Government. Peter Hall, taking over, had to make the best of the project, in his own words, approaching the building as a ‘found object’. Some plans were revised: Utzon, for example, wanted a lush red and gold ceiling and boxes in the Concert Hall, blue and silver in the Opera House.

Stephen CoburnHe was a very gentle man. He just took it on the nose, really. The most important thing to him was that the curtains were made.

An Australian agent for the Aubusson Tapestry Workshop, where the artworks were created, Lucien Dray approached Coburn with the original proposal for collaboration and expedited the Coburn family’s move to France while the tapestries were made. They ended up staying for three years and Coburn’s works there included his large scale The Seven Days of Creation, which was presented by the Australian Government to the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, and some smaller works. Dray facilitated the negotiations between Hall that Coburn design tapestry curtains for the theatres. Hall agreed.

“He was a very gentle man”, Stephen Coburn told a journalist after his father’s death in 2006. “He just took it on the nose, really. The most important thing to him was that the curtains were made.”

Conserving the curtains

In the years since the curtains have been in storage, many calls have been made for them to be brought out again: newspaper articles, letters to editors, public campaigns. Sydneysiders have seen them again once or twice for brief periods, as an exhibition of Coburn’s exciting work rather than as working proscenium curtains. In the 1990s they were taken out for cleaning, assessment and major repair by the Victorian Tapestry Workshop (now the Australian Tapestry Workshop). When Coburn died in 2006, they were hung again on two consecutive Sundays in the theatres as a tribute to the artist.

In 2017, the Opera House engaged International Conservation Services to assess the condition of the tapestries, including their ability to be rehung. They found that the tapestries were in excellent condition overall, with no sign of deterioration since repair works were undertaken in the ‘90s. Despite this, the assessment indicated that the tapestries would deteriorate if used as functioning curtains again.

Stephen CoburnI’ve been trained as a conservator. I think in thousands of years. The curtains have universal themes that will be relevant in perpetuity.

Anne Watson, whose recent book The Poisoned Chalice: Peter Hall and the Sydney Opera House, traced the goings-on during construction and wrote in a research paper commissioned by the Opera House that “Coburn’s prominent place in 20th century Australian art is unassailable. The Sydney Opera House tapestries are generally regarded as amongst his most significant works and Coburn himself felt they were his ‘greatest art works’.”

Watson refers to the art critic John McDonald, who admired Coburn’s work. He can be critical of abstraction but wrote these words of Coburn’s tapestries in 2006: “His work will always be recognised as an art of affirmation, by turns cosmic and intimate. It is a rare distinction for an artist to have cast off the gloom and the angst of the modern era, and to come out on the side of the angels.”

With the tapestries’ condition now confirmed, they are ready to grace the stages once again and will be displayed as part of a public guided viewing on 22nd May 2019. This special viewing is part of the Opera House’s ongoing heritage interpretation program, which includes a range of activities to engage the community in the building’s heritage. As part of this work, the Opera House is committed to exploring options for longer-term hanging of the tapestries, more regular short-term exhibitions in the venues.

Stephen Coburn, who is also an artist and conservator, is philosophical about the longevity of the tapestries’ significance.

“The curtains are superb examples of our father’s art, and possibly his finest. They’re breathtaking illustrations and create a great sense of warmth, excitement and anticipation when seen in the theatres.

“As works of art, they evoke universal themes that will be relevant in perpetuity.”

He knows people will appreciate his father’s brilliant curtains when they shine again this year.

Miriam Cosic is a Sydney-based journalist and author. She an art critic at The Saturday Paper. Twitter @miriamcosic

This article is based on research undertaken by Dr Anne Watson on behalf of the Sydney Opera House. The Australian Government has kindly provided funding support for the exhibition through its Protecting National Historic Sites Program.