Under the Sails with the London Symphony Orchestra

Published

In our 50-year history, the Sydney Opera House has welcomed thousands of world-class performers to its halls. Great musicians such as operatic diva Joan Sutherland and pianist and conductor Vladimir Ashkenazy, and international orchestras such as the Berlin Philharmonic and the Israel Philharmonic, which has visited no fewer than five times! But no orchestra has as long and rich a shared history with the Opera House as the London Symphony Orchestra.

Picture this: The musicians of the London Symphony Orchestra arrive at the Sydney Opera House – suits and ties to a man. The occasion seems formal. But the news camera has panned past the raw scaffolding of the shells, and in the foreground a worker is laying shimmering white tiles in their signature chevron pattern.

It’s 1966. Australia has just switched to decimal currency, and the LSO’s concerts here have been advertised in dollars and in pounds. (The best seats were $4.55 or £2/5/6.) Not only is the Sydney Opera House unfinished, but it has reached a tumultuous point in its construction history, with the resignation in March of architect Jørn Utzon.

On that first Australian tour, the LSO’s Sydney concerts take place in the Sydney Town Hall. But even so, the orchestra’s connection to the the Sydney Opera House is already being forged. The Cleveland Orchestra will be the first international orchestra to give a concert in the newly opened Sydney Opera House in 1973, but the LSO is the first to play there, even before the building is complete.

Framed by exposed masonry and concrete, with their principal conductor István Kertész at the podium, the LSO performs Schubert’s Ninth Symphony for a small audience of workers and guests. There’s no audio on the old newsreel, so we can’t hear the result, but the reports aren’t exactly encouraging.

“Bad acoustics in new theatre” reads the headline; the acoustics of the unfinished theatre were “terrible”, said Kertész. But this was hardly surprising, and he wisely added that he would withhold a definite opinion until the building was finished. Meanwhile, the building “could become one of the ‘seven wonders of the world’”, and the LSO’s manager at the time, Ernest Fleischmann, described the Opera House as Australia’s “cultural ‘coming of age’”.

Strictly speaking, the LSO–Sydney Opera House connection had begun years earlier. It was one of the LSO’s longstanding conductors, Eugene Goossens, who – as chief conductor of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra and director of the Conservatorium – had been a tireless advocate for the building of an opera house in Sydney, confident that Australia could take its place on the world stage with a truly first-class venue for music, opera, ballet and theatre.

In 1950, Goossens issued an ultimatum to the NSW Government: “Either we start a Sydney Opera House now – or I leave.” As it happened, construction didn’t begin until 1959, by which time Goossens, forced out by scandal, had returned to London where he’d begun a series of recordings with the LSO, including the landmark Australian work Corroboree, by John Antill.

The reports don’t say exactly where in the Sydney Opera House the LSO played in 1966, but at that point one of the most significant decisions was still to be made: the ABC's claiming of the “main hall” as the principal venue for the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. Today we take it for granted that a visiting orchestra will perform in the Concert Hall, and it’s noteworthy when opera, dance or a play like Amadeus is produced in that space.

It wasn’t conceived that way, however, and in December 1966, another LSO connection flew in to Sydney to advise on the subject. Ernest Bean had managed the rebuilding of London’s Royal Festival Hall as a permanent home for the LSO, working with talented young architect Leslie Martin. (In another link, Martin had been one of the judges for the Sydney Opera House design competition.) Now the NSW premier, Robert Askin, wanted Bean to investigate whether the main hall should be retained as a theatre for opera and ballet, as originally planned, or be adapted for concerts, as the ABC wanted.

Kertész died before the Sydney Opera House opened, so he never had a chance to revise his assessment. But the LSO did return to Australia and their second tour, with Claudio Abbado conducting, coincided with the Opera House’s tenth anniversary in 1983.

For that visit, the LSO’s programs included English repertoire (Elgar), Mahler to fill the hall with exhilarating sound and extremes of emotion, and a thrilling all-French program with La Valse by Ravel and Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. Ever since the 1960s, when Pierre Monteux was the LSO’s principal conductor, French music had been part of the orchestra’s DNA. As Sir Simon Rattle puts it, a London group has turned out to be “one of the great French orchestras”, and that quality is on show this year as the LSO plays to its strengths.

Living music

The LSO was again playing to its strengths when it returned to the Sydney Opera House in 2014 with muscular, high-energy performances of 20th-century Russian classics: Prokofiev symphonies, Stravinsky ballet music, Rachmaninoff riches.

The programs in 1983 and 2014 appealed to a heartland audience and all of it was great music. Even so, it’s difficult not to feel nostalgia for the 1960s programming. For that first Australian tour, the LSO brought more than 14 different works, including four by living English composers, one of them specially commissioned. And four of the orchestra’s principal players appeared as soloists, including the Australian horn player Barry Tuckwell who, in addition to playing a Mozart concerto, gave the local premiere of another newly commissioned work, a concerto by Australian Don Banks.

In this year’s tour we again get to hear living composers. American John Adams – a dear friend of Sir Simon Rattle – is represented by his phenomenal Harmonielehre, and there’s a new commission by London-born Daniel Kidane, Sun Poem – music that finds inspiration and beauty in his Eritrean and Russian heritage.

And while there are no concerto soloists this year, the Australian presence in the London Symphony Orchestra continues to make itself felt. Among the touring musicians are two Australian violinists. Naoko Keatley graduated from the Sydney Youth Orchestra to the Royal Academy of Music in London and into the orchestral scene of one of the most musically vibrant cities in the world. She joined the LSO in 2014.

Belinda McFarlane studied in Adelaide and played in the Australian Youth Orchestra before making her way to London. She’s been a member of the LSO for more than 30 years, and is a key participant in the orchestra’s Discovery team and education committee. This work is what enables the LSO to deliver inspiring creative-based education programs, as they did in 2014, working with students from throughout NSW.

The depth of McFarlane’s role with the LSO is a reminder of the orchestra’s special history. Most of the world’s great orchestras were formed by and as institutions. But the LSO began life in 1904 as a breakaway ensemble, rebelling against Henry Wood’s demands that the musicians in his Queen’s Hall Orchestra play exclusively for him and not send deputies when they wanted to take on better-paid gigs elsewhere. For the first 40 years the LSO functioned as a profit-sharing co-op, and the orchestra continues to choose its own principal conductors and appoint the chair from within its ranks. Tuckwell, for example, was the Chair from 1962 to 1967.

Sydney is a culturally rich city, but when it comes to orchestral music, London is something else again. No other city in the world supports so many symphony orchestras that they have to maintain what’s known as the “Clash Book” – negotiating programming with each other to ensure that London audiences aren’t offered, say, three different Mahler Ones in the same week!

One offshoot of the wealth of orchestral activity in London is that an orchestra like the LSO has traditionally spent a lot of time touring. For an orchestra like the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, an international tour is a major undertaking that occurs at most once every few years, and it’s a reputational exercise rather than a money-making one. A London orchestra, on the other hand, tours frequently (global pandemics permitting) and, for the most part, tours are expected to pay their way.

Even so, a tour like this final one with Sir Simon Rattle is a big deal: as much as special event for the LSO as it will be for the audience. It’s significant that the LSO has chosen to bring music that, under normal circumstances, would be considered “too big” to tour. Harmonielehre, for example, requires more than a hundred musicians, including two harps.

Of course, if you’re bringing two harps, a big percussion section and someone to play the “sugar plum” celesta for one work, you may as well make good use of them, and Sydney audiences will get to hear the LSO in the second suite from Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé ballet, Mahler’s Seventh Symphony and a brilliant, youthful piece by Stravinsky, Fireworks.

Monumental Bruckner

Bruckner’s Seventh Symphony – in a program exclusive to Sydney – will make its own monumental effect. “Cathedrals of sound” is a Bruckner cliché in large part because it’s true. It’s also true that the very best way to hear a Bruckner symphony is in a magnificent hall. Where Bruckner is concerned, no recording, no sound system, can match the live concert experience.

Could this be why, despite having made more recordings than any orchestra in the world, the London Symphony Orchestra had never recorded Bruckner Seven until just last year? (It’s in the can but still to be released.) Whatever the reason, Simon Rattle has now filled a glaring hole in the LSO discography.

Sir Simon is a Bruckner champion, delving deep into the music and the composer’s intentions. The performance of Bruckner Seven he conducts in Sydney will be the first Australian outing for a new edition, prepared by musicologist-detective Benjamin Cohrs. The differences are technical on paper (something for the aficionados), but as Sir Simon points out, what might feel like small details can accumulate to create fascinating new colours (which anyone can hear).

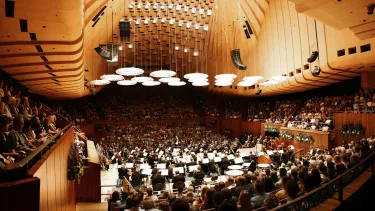

Best of all, any complaint that the Concert Hall isn’t up to the Brucknerian “quest for cathedral echoes” (according to a critic in 1973) is now a thing of the past. If you want to experience the full effect of the hall’s renewed acoustic, Bruckner Seven could well be the piece to hear.

Turning full circle

The attractions of exclusives aside, no orchestra in its right mind crosses the world simply to perform in one city. In 1966, the LSO landed in Perth and made its way anti-clockwise to Sydney via the Adelaide Festival and Melbourne. This year, they’re repeating their 2014 itinerary by travelling in the opposite direction: Brisbane’s QPAC, Sydney and on to Hamer Hall in Melbourne.

This tour might represent Sir Simon Rattle’s final tour with the LSO, but in other respects it’s a tour of firsts. Since the LSO’s previous visit to the Opera House in 2014, the Concert Hall has been renovated, with new acoustic panelling and reflectors, and the installation of a stepped concert platform. The acoustics of the completed hall were never “terrible” as Kertész claimed, but they weren’t quite what musicians and audiences had hoped for either. If Kertész were alive today, he’d probably be impressed with its transformation. And, just as the LSO was the first international orchestra to fill the Sydney Opera House with symphonic sound in 1966, so it has the honour of being the first international orchestra to perform in the renovated hall, bringing Sydney, and the LSO, full circle.